TIME

April 20, 2001

Kobans and Robbers

An obscure Japanese import is racing across America

-- reducing crime and increasing safety along the way

By Barry Hillenbrand

|

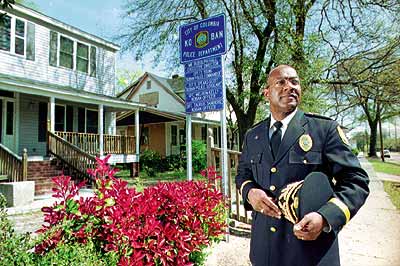

| Columbian police chief Charles P. Austin credits koban, Japanese-style police stations, for bringing officers and communities together. |

It is 5:15 in the afternoon. Prime time for kids looking for some action. Fooling around time. Getting into trouble time. Outside of one of the units of Latimer Manor -- a low-rise public housing project in Columbia -- a group of teens in baggy pants and cornrow hairdos are talking with patrolman Arthur Thomas. Two police cruisers are parked at the curb.

It has all the looks of a tough day in the projects. A bust going down. But Thomas is just hanging with the kids. "It's part of my job," he says. His job has lots of parts -- patrolman, community worker, role model. A tall bruiser of man Thomas grew up in Columbia's public housing and now works out of a police substation located in a pair of converted apartments in the Latimer project. The sign out front says "Koban," what the Japanese call their ubiquitous police mini-stations. Tiny, cramped kobans are everywhere in Japan: next to the local vegetable store in villages, on busy downtown shopping streets, across from parks, near schools -- more than 6,600 of them nationwide. And increasingly they are popping up in the U.S. as well.

The koban idea snuck into America largely unnoticed in the 1990s along with boatloads of other Japanese imports. It was carried in by American police officials who had journeyed to Japan in search of some explanation for the island nation's low crime rate. Kobans, which put police and citizens in close, personal contact, were apparently part of the answer: they stood in marked contrast to the anonymous police in patrol cars cruising America's streets. Aided by grants from Japanese corporations and U.S. government money funneled through the Milton S. Eisenhower Foundation, an offshoot of the Kerner Commission that studied the causes of the riots that plagued U.S. cities in the 1960s, several American police departments have tested variations of the koban concept. "When I saw how kobans worked, I said, 'I've got to copy this idea,'" says Thomas Frazier, who visited Japan when he was police chief in Baltimore, Maryland, during the 1990s. "We had been talking about community policing for years. The koban allowed us to create an institutional anchor in neighborhoods where officers have face-to-face contact with the public."

Frazier had an architect design a koban for Baltimore's Howard Street, a busy -- but crime-troubled -- downtown avenue near a bus and rail-line junction. The police who staff the koban patrol the surrounding streets, offer help to lost visitors and keep an eye on the video screens of the surveillance cameras that pan the area beyond the officers' view. "It makes a difference," says Tom Yeager of the Downtown Business Alliance -- and a former Baltimore cop. Since the koban was installed in 1998, the number of purse snatchings, pickpocketings and muggings in the area has been reduced.

When Charles P. Austin, Columbia's police chief, visited Japan in 1994, he found that the Japanese koban idea meshed perfectly with a program he had already begun of stationing police in the city's neighborhoods. He slapped "koban" signs on the side of existing substations and started new ones. "The Japanese name and concepts invigorated our program," says Austin. "Young officers were very enthusiastic to join." Officers like Thomas, who revels in the close contact he gets with the community. "There's often a negative attitude toward police on the street," says Thomas. "But koban gives the public a different view. I'm here to show them that we want to help you, not to lock you up."

Austin added features to his kobans not found in Japan. Columbia's kobans offer a team of civilian staffers to work with the hordes of kids who come swarming in after school hours looking for a place to do homework, play on computers or just hang out in safety with their friends. A koban to these kids has less to do with police work and is more like an after-school club.

At the koban located at the W.A. Perry Middle School, in Barhamville, a neighborhood where brightly painted upper middle class houses are mixed with public housing units, a kid named Parrish drops his violin case and book-heavy backpack on the floor and goes to see James Bulger, the koban's program director. Parrish, 12, has a litany of problems. He's been suspended from school for talking and misbehaving in class. He occasionally misses taking his medication for hyperactivity. He shuttles between his grandmother's apartment and that of an aunt. His life has little stability -- except for the koban, which provides homework help, a bit of shelter and Bolger as a clear role model. "Parrish is a great kid," says Bolger. "He's got nowhere to turn. We might just be able to keep him out of trouble."

Outwardly, Columbia's noisy and chaotic kobans -- with their craft classes, field trips, sports teams, teen rap sessions -- may bear little resemblance to Japan's utilitarian, spartanly furnished originals. But, says Chief Austin, "we're trying to achieve the same thing. In Japan the police have a sense of belonging and of being accepted in the community beyond their role as police officers. That was an advance we wanted to bring here."

And an advance in neighborhood solidarity and safety is precisely what's happened. In the Lyons Street neighborhood, once a combat zone bullied by drug pushers and teenaged hoodlums, violent crime is down 15% since the Gonzales Gardens koban was opened there in 1995. In the areas around kobans, calls to the police emergency telephone number 911 reporting dangerous situations have been reduced by a half. Now other neighborhood groups in Columbia are clamoring to have kobans of their own. Nationally, grants from the Eisherhower Foundation have opened kobans in places like Kansas City and Dover, New Hampshire. The kobans success may not rival Pokémon. But it's not a bad record for an obscure Japanese import.

[ Back ]