Journal for Nonprofit Management

Lessons from the Street: By Lynn A. Curtis Some community economic development corporations have experienced considerable success partly because of the emergence of solid technical assistance and training opportunities for them over the last twenty years. However, we know less about how to best provide technical assistance and training for capacity building and replication to inner city, grassroots, nonprofit organizations working in "softer" fields like child and youth development, public school innovation, job training and placement, advocacy, crime and violence prevention, drug prevention, and community-police partnerships. This article is primarily about those latter groups. It is based on the Milton S. Eisenhower Foundation's street level experience from 1990 to 2000. During that time, the Foundation sought to enhance the capacity of, or host replications in, eighty-one nonprofit organizations in twenty-seven states, the District of Columbia and Puerto Rico. Those groups had annual budgets that ranged from $45,000 per year to well over $1M per year. Almost all were African American, Latino or Asian American, inner city nonprofit organizations. The Eisenhower Foundation financed capacity building, replication, or both, through grants from eleven foundations, four federal departments, eight major corporations and over fifty other national and local matching partners. For some replications, police chiefs in eleven cities supplied officers as in-kind match to work with civilian staff (Curtis, 2000). Several evaluations were undertaken on this work. In what follows, the main findings are summarized, lessons for practitioners and funders are set out, and tentative conclusions are reached on how to build capacity and replicate at a scale equal to the dimensions of the problem. Findings The Foundation used the following technical assistance model for its capacity building and replication efforts (Figure 1). Figure 1 The Foundation began by providing capacity building assistance, technical assistance in replication, funding to sites, or some combination. This, we anticipated, would result in improvements in skills, knowledge and action by the nonprofit organizations. We then anticipated measurable outcomes that could be attributable to the improved skills, knowledge and action. For example, such outcomes might include more funds raised by the organization or better school performance by the youth served by the organization. The cause-effect relationships we posited did, in fact, operate for capacity building as well as for replication based on findings from several outcome evaluations as well as on a decade of process evaluations (Curtis, 2000). We found that technical assistance can create positive change, including technical assistance in evaluation and in communications, areas not always covered in the field of nonprofit capacity building. The nonprofit organizations we trained felt strongly that every one of these technical assistance areas impacted on every other area. For example, board development facilitates fundraising. Unless programs are well managed financially, they are unlikely to be successful, which makes fundraising and board recruitment more difficult. Skill with media can lead to more visibility and hence income. If new board members are selected carefully, they will bring in ideas for new programs and can access new funding. We concluded that a well-developed technical assistance work plan must create these linkages for any one organization. Funders need to avoid restrictions on technical assistance providers and nonprofits making such linkages. We were almost always successful in using Eisenhower Foundation technical assistance to foster improvements in skills, knowledge and action by grassroots, nonprofit organizations. In the case of capacity building, there were good examples of measurable outcomes such as more funds actually raised and improved performance of youth served by a program. But examples of measurable outcomes were not as frequent as examples of improvements in skills, knowledge and activities by the nonprofit organization. In other words, for capacity building, we found changes in skill and knowledge easier to come by than changes in outcomes. Consequently, we concluded we needed to provide capacity building technical assistance to any one site for periods of twenty-four to thirty-six months in order to generate more fully measurable outcomes. In the case of replication, there were many improvements in skills, knowledge and action as well as many measurable outcomes. However, grassroots organization staff members believed too often that "success" was at hand as long as there were demonstrable improvements in their skills, knowledge and action. This failure to translate organizational improvements into measurable outcomes is, perhaps, not surprising. The failure is all too apparent in the context of national, private and pubic policy in America that seeks solutions to inner city problems. In the case of "welfare reform", "success" has been claimed by some on the basis of reduced welfare roles. But taking people off welfare rolls is an organizational action. "Welfare" originally was designed as an intervention to reduce child poverty. Hence, the outcome measure for "welfare reform" is reduced child poverty. Child poverty did decline in the 1990s, but it is virtually impossible to tell whether the main reason was the booming economy or "welfare reform" (Curtis, 2001). Accordingly, we need more careful technical assistance to better teach grassroots organizers, as well as policy makers, the difference between actions taken and outcomes achieved. Examples of the Technical Assistance Provided Board Development Many agencies had similar, and in some cases severe, problems with their board of directors. There typically was a need for better understanding of the board members' roles and responsibilities, improved effectiveness of board committees, and increased board involvement in fundraising. Foundation staff reviewed materials from nonprofit groups that defined board roles and responsibilities, observed board meetings, and assessed the degree of board involvement of the executive director and of individual board members. For many groups, staff and trustees were equally unclear about board roles and responsibilities. One change often recommended was to increase board diversity, in terms of skills and ethnicity. For example, attorneys formed the majority of the board of one group we assisted. One trustee or another often postponed board votes because of concern over legal implications. The board was ineffective. After revising the by-laws and electing a new executive committee, the agency recruited more nonlawyers, and some of the earlier deadlocks were resolved. The Eisenhower Foundation provided board members with materials from the National Center for Nonprofit Boards that explained board member fiduciary and policymaking roles and responsibilities. When assistance was given to boards, we appeared successful in changing board members' understanding of their fiduciary and policymaking roles, encouraging changes in board composition, and impressing on trustees the need for financial support. However, in most cases, ultimate measurable outcomes remained uncertain at the time we completed assistance, usually after twelve or eighteen months. In many cases, it still was not clear whether board members were merely giving lip service or were prepared to act. One chair had insufficient time for his duties, but would not alter his role. Out of frustration, the executive director threatened to resign. We persuaded her that she would be of more value to the organization if she stayed and tried to reshape the board slowly over time. Fundraising Over the ten years of work reported here, nonprofit organizations requested fundraising technical assistance from the Foundation more than any other kind of assistance. Given this interest by nonprofit groups, it is perhaps not surprising that Foundation technical assistance appeared more effective for fundraising than for any other area of capacity building. One popular Foundation role-playing workshop helped nonprofit organizations practice presentations to funders. All participants were nonprofit organization staff, but some played the role of grantmakers. The rest made their cases as prospective grantees. The grantmaking role players had $2 in quarters to distribute. The first round of the exercise ended with one presenter getting most of the quarters, two others getting some quarters, and the rest getting none. The exercise helped teach participants how difficult funding decisions could be with scarce resources. It also pointed to the importance of developing quality presentations that led to financial support. Many nonprofit organizations habitually apply to the same funding sources and are unfamiliar with other funding options available to them. Foundation assistance articulated such options. Several organizations carried out capital campaigns. One executive director was encouraged to take greater risks in applying for funds. She submitted proposals to several sources and delivered her message effectively enough to secure grants from all of the new funders who received applications. Her boldest move was to develop a collaborative grant request that involved working with an established organization to provide services and training to clients in Russia. The proposal was funded. She attributed her fundraising success to the skill development she garnered from Foundation fundraising workshops. Basic to this success, and to similar success with other nonprofit organizations, was the Foundation's insistence on a balanced portfolio, including but not limited to individual donations, corporate grants, foundation grants and public sector grants. Each source has its costs and benefits, and the optimal strategy, we taught local groups, is not to become trapped by an over reliance on any one. Financial Management As part of the initial needs assessment, the Foundation reviewed the fiscal management of nonprofit organizations, determining what record-keeping policies and procedures were in place, who was responsible for accounts payable and receivable, who signed checks and under what circumstances, whether state and federal guidelines were being followed, what the budget process entailed and what programs and equipment were in place to facilitate the process. Because all funders require some demonstration of ability to manage funds, each of the agencies had some procedures in place. Foundation staff helped to make the agency's systems operate more efficiently, and they helped executive directors provide adequate financial reports to boards of directors. All of the organizations we assisted underwent annual audits. The most common fiscal problem was when the board of directors did not properly exercise their financial oversight usually because of weak finance committees. The Foundation sought to strengthen those committees. Groups with fiscal management difficulties were especially likely to encounter multiple capacity building problems (board development, fundraising, and staffing). We sought to work through the problem linkages and common origins with such organizations. In several cases, the Foundation examined accounting software that was in use by the organization and made recommendations for improving the system. One group had software that could only be used on one computer and was not transferable to other computers on site. In response to the Foundation's recommendations, this organization hired a part-time accountant who consulted with the Foundation's chief financial officer to develop a system that worked more efficiently. Perhaps our clearest financial management success was with an organization in trouble with the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) for not having paid payroll taxes for several years. The Foundation's chief financial officer secured power-of-attorney and interceded on behalf of the organization in negotiating with the IRS for payment of back taxes. He also convinced the organization to hire a part-time accountant to assist with managing finances. These are proximate outcomes. The ultimate measure of success -- still unrealized -- will be when the organization can, for example, utilize its improved standing with the IRS and its new accountant to attract more grants, improve staff morale, bring on trustees with more confidence in the organization and motivate those trustees to raise new funds. Organizational Management and Evaluation. The Foundation's greatest success in organizational management over the years was in teaching improved accountability. Foundation needs assessments frequently showed that lines of accountability were unclear in many grassroots organizations. The Foundation therefore created an accountability workshop as part of its group training. The accountability workshop was popular with participants. The reasons for success were that:

Originally perceived as an abstract concept by many participants, "accountability" was made more concrete by a trainer who was "in the same shoes" as the trainees. The training sessions ended with each agency presenting an "in-service training plan" that gave the dates on which each would conduct training at home agencies. Six months after the training, each organization was asked to forward materials showing whether and to what extent other staff had been trained. Copies of accountability matrices for all staff were submitted. Other areas of organizational management assistance proved more challenging. Grassroots nonprofit executives typically did not understand the distinction among foundation inputs; consequent local organization improvements in knowledge, skills and action; and consequent measurable outcomes (Figure 1). This we saw as a problem in organizational management. Many local staff thought the end consisted of improvements in knowledge, skills and action. While such changes are crucial for evaluators to document, evaluators look for consequent measurable outcomes like more money actually raised in the case of fundraising. If nonprofit executive staff is implementing programs with different ends in mind than evaluators, the resulting evaluations may disappoint the organizations being evaluated and their funders. Program staff and evaluators need to be on the same page. Our workshops on input-outcome evaluation thinking and its relation to management by objective usually received high ratings. But we concluded that these lessons need to be repeated again and again, in group and one-on-one settings. Another illustrative organizational issue we faced was excessive control of organizations by the larger organizations in which some were located. Over the years, we experienced at least three instances where youth serving organizations were stymied by the economic development organizations in which they were components. In one case, the smaller, youth serving component had a number of problems, but also many successes and considerable promise. The Foundation provided needed proposal writing assistance, so the organizational component could continue after support by an initial funder ended. However, the overall economic development organization did not support continuation (for reasons that never were shared with us), so the initiative shut down. In the second, somewhat similar case, the highly structured economic development staff of the host organization did not feel comfortable with the unstructured style of the youth development program staff. In the third case, the youth program performed well, but the overall nonprofit economic development organization was poorly managed. In spite of Foundation efforts to improve management, the economic development organization closed down, causing the youth component to close down as well. Technical assistance funds ran out, and the Foundation was unsuccessful in an attempt to help the youth group incorporate separately. An organizational lesson here, therefore, is caution against selecting organizations that are components of larger organizations, with missions that are not completely in sync and staffs that may possess different styles and skills. In our experience, such dysfunction is especially possible in marriages between economic development and youth development nonprofits. The former often have the financial resources to begin youth development components, which then appeal to youth in unstructured ways that may be inconsistent with the more structured, business-like style possessed by many economic development staff. However, with careful communication and a cooperative overall director, such partnerships are not impossible, as we found in New York City in a successful youth and community initiative with the Mid-Bronx Desperados Community Housing Corporation. A final illustration of the organizational management issues we faced was the almost universal need for more modern computers and associated software, Internet access and training. Good nonprofit managers need information; tools to organize and help manage their usually extended, stressful and often chaotic day; improved filing systems to keep track of documents, especially given inadequate numbers of well-trained support staff; and quick ways to communicate with board members. Unfortunately, none of the grants used to finance the Foundation's capacity building work had sufficient funds to address these hardware, software and training needs. Personnel Management Besides providing model personnel manuals and evaluation forms, the Foundation assisted organization founders who recognized the need to delegate more. A person with the talent, courage and tenacity to create an extraordinary oasis in the middle of an inner-city ghetto founded one group. As required by the group's by-laws, a majority of the board was composed of community residents. The requirement led to recruitment of trustees who meant well but who were otherwise limited in their contribution to the agency. Our technical assistance consisted of a series of "coaching" sessions with the executive director, convincing her of the necessity to build a stronger board as the only way to achieve her stated objectives. The executive director eventually embraced this approach. New members were added to both the community and non-community components of the board. The board went through a Foundation training session on its roles and responsibilities and gradually became more involved in the substantive decisions of the agency. Lessons Learned 1. Future Progress in Capacity Building Will Be a Function of Adequate Resources, Regional Clustering and Distance Learning We found that grassroots nonprofit organizations that best respond to technical assistance and training typically are in the "pre-takeoff" stage (often three-to-five years old), have some solid capacity in place and often operate with budgets in the $150,000 to $600,000 range. Not uncommonly, such groups exhibit an enthusiasm to learn, a commitment to stay with the technical assistance over many months, and a desire to pursue multiple technical assistance linkages. For such groups, the assumption we developed over time was that we needed one technical assistance and training director (who also had at least one area of substantive expertise) and two full time equivalent technical assistance providers for every ten sites, over twenty-four to thirty-six months of assistance. We concluded also that each grassroots group should receive a discretionary grant of at least $10,000. Such a grant immediately establishes the seriousness of a commitment to change and allows local grassroots organization staff greater clout in effecting change. Grants of this kind are a much-needed financial boost to many grassroots organizations, which are being asked to make major investments of time. Regional clustering of sites creates economies of scale for technical assistance. Given that tens of thousands of nonprofit groups are in need of capacity building technical assistance in America, any serious effort to provide sufficient assistance requires both national and regional intermediaries. There should be uniform standards in terms of quality and quantity of staff and consultants, ratios of providers to sites, technical assistance provided, areas of assistance covered, and length of time assisted. Capacity building for the thousands of nonprofit organizations currently in need of technical assistance and for new groups would seem a daunting endeavor. However, distance learning could provide a cost-effective breakthrough to allow, over time, assistance to all groups in need. Established funders and new grant makers with endowments from high technology fortunes need to support a series of demonstrations to learn just how far we can proceed and how successful we can be with nonprofit distance learning in capacity building and replication with pre-takeoff groups. Our experience suggests that hands-on in-person training will continue to be essential, but that committed grassroots organizations can make great progress using clear, well-packaged, peer-based distance learning training that fits their busy schedules. 2. Beware of Rhetoric that Substitutes for Resources The corollary to the need for sufficient dollar resources for capacity building and replication is the need to question rhetoric that downplays or obscures adequate funding. Examples include fashionable phrases like: "volunteerism", "self-sufficiency", "empowerment" and "faith-based". To illustrate, the highly publicized 1997 bipartisan national summit in Philadelphia on voluntarism has been viewed with skepticism by many observers. At the time of the summit, the New York Times interviewed residents in the impoverished Logan neighborhood of North Philadelphia. One resident thought that the summit was a bit "naive" because "you need a certain expertise among the volunteers, and in communities like Logan, people do not have the expertise" (Belluck, 1997). The director of a non-profit community program in the neighborhood observed, "Volunteering is really good, but people need a program to volunteer for, and in order to do that, you have to have dollars." Pablo Eisenberg, former Executive Director of the Center for Community Change and now a Senior Fellow at the Georgetown University Public Policy Institute, concluded that "no matter whether you attract lots of volunteers, money is still the most important ingredient in reducing poverty and helping poor people. You need money even to organize volunteers" (Bennett, 1997). After describing how volunteerism increases the gap between rich and poor (because most volunteers tend to stay in their immediate social and economic world), Sarah Mosle concludes a New York Times Magazine article by showing that public resources must drive private volunteerism: "Government spending causes volunteering. You can't have a volunteer in a school without a schoolhouse. Government institution building increases volunteering" (Mosle, 2000). America won the war in the Persian Gulf because of large numbers of well-trained professional staff, large numbers of well-trained support staff and a huge amount of high quality equipment. Yet, when it comes to the inner city and the truly disadvantaged, we are told that there is not enough money for adequate and adequately paid professional staff, adequate and adequately paid support staff, and good equipment like computers and facilities in public schools and at the headquarters of the inner city, grassroots community-based nonprofit organizations that are responsible for a great deal of what works. Instead, we are told, for example, that a grassroots community group ought to get new revenues from charitable tax deductions or grants from the public private sectors for eighteen to twenty-four months. Then it ought to convert into "self-sufficient" operations by using a lot of (often poorly trained) volunteers from suburbia who "are here to help you." Volunteers should be combined with "partnerships" and "coalition building" among other financially competing and often penurious groups in the inner city. This, we are told, will somehow lead to the "empowerment" of our neighborhoods and our schools. But it does not work that way, as anyone outside of Washington who labors in the trenches in the inner city knows. Similarly, there presently is much debate on increasing the role of "faith- based" nonprofits. Over the years, the Foundation has undertaken replications with both secular and "faith-based" grassroots nonprofit organizations. Our experience and that of others suggest that the batting average of "faith-based" groups is not higher than that of secular groups. The key to success is not whether a nonprofit group is secular or "faith-based". The key is whether an organization has sound institutional capacity. And institutional capacity requires resources. 3. For Capacity Building, Mechanical Change is Easier Than Behavioral Change At least two types of change occur within an organization receiving capacity building technical assistance and training:

Mechanical change tends to be rather straightforward. You have policies or you do not. The policies are effective or they are not. Such change is relatively easy to make once the key executives involved realize that the change improves their operations and makes them appear more efficient. Behavioral change is the more difficult of the two. It tends to focus on people, rather than on systems. Therefore, it often requires altering long-held beliefs and "ways of doing things" that, however time-consuming or inefficient, are nonetheless "comfortable" and highly resistant to alteration. This is the form of change that can underlie resistance to seemingly "easy" mechanical changes and delay or even sabotage them. It also may explain the continual delays, postponements and obfuscations that prevent "getting things done". Such behavior seems to be associated with people who have been with their organizations for a long time and have become accustomed to doing things in a specific way. It takes time to recognize the need for such behavioral change. When the need for change is recognized, it may require a degree of coddling and nagging, or both, by the technical assistance providers to convince the person to begin to change. It takes more time for these changes to be implemented, and once the changes are begun, continuing midcourse corrections are needed. Such changes require a tremendous amount of trust between the technical assistance provider and the grassroots organization staff and trustees, because a great deal of personal power and prestige are involved in these changes. Such trust requires high levels of professional and interpersonal skill by a senior technical assistance provider. 4. To Qualify As a Model for Replication, a Program with Capacity in Place Should Be Scientifically Evaluated In terms of personal and public health, Americans tend to accept the notion that new drugs to fight, say, cancer or AIDS need to be scientifically evaluated and that, if they work, there then should be widespread use of them among all in need. For the truly disadvantaged, a few instances can be found of replications that follow such a reasonable course. One example is the Ford Foundation's Quantum Opportunities Program, based on adult mentors for inner-city high school youth. After Brandeis University released statistically significant findings that showed Quantum Opportunities worked and could be replicated, the New York Times published an editorial summarizing the success (New York Times, 1995). Quantum Opportunities now is being replicated on a broader scale through public and private funding. Yet the example of Quantum Opportunities is relatively rare. Especially for public sector funding, programs for the truly disadvantaged can be replicated because of the influence of well paid lobbyists, access based on friendships, and fashions of the moment, not because of positive evaluations. We believe that funders should use scientific evaluation and not political ideology to decide whether a model is qualified to be replicated and that a replication has worked. By "scientific evaluation", we mean use of a control group or comparison group outcome measure design, implemented over sufficient time -- not just in a narrow, academic way but also in the rough-and-tumble of real world street life, funding, pressure, staff burnout, inadequate salaries and political machinations. Many successful models provide multiple solutions to multiple problems, and good evaluations must capture this reality. 5. Replication is Possible Some assert that it is impossible to replicate successful grassroots nonprofit successes, in part, we are told, because such successes depend on charismatic individuals who cannot be duplicated. That is not so. Replication is quite possible. We found that it depends on:

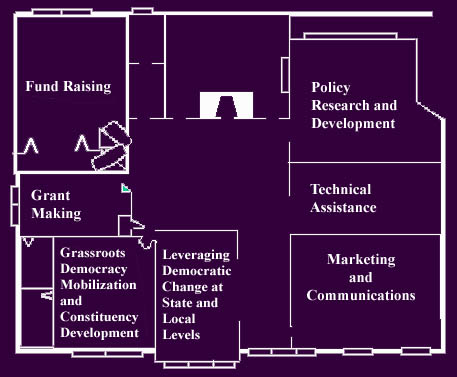

It is possible to be successful with replications that are as close to duplications as possible. Many funders, especially public bureaucracies, can insist on duplication as the goal. In spite of achieving positive outcomes with such duplications, the Eisenhower Foundation has experienced even better outcomes when it has replicated the principles underlying the model program. The essence of the model is replicated but variations on the theme are allowed so that local implementers can have more ownership in the process of replication and the strength of the outcomes. With this definition of replication, it also is easier than with exact duplications to adapt to local circumstances. A model program can be replicated entirely at another location. It also can be replicated at a host organization that already is working the field and has some of the model's components in place. The Eisenhower Foundation has had positive experience with each variation. When the model is replicated in its entirety at a new location, sometimes there can be a rather slow replication start-up period and considerable staff turnover, as new ideas are put into practice and some personnel do not meet expectations. The advantage to replicating the entire model can be local enthusiasm for exciting new ideas and little resistance to implementing them. When the host organization already has some of the components of the model in place and is integrating other components that it does not have, there can be institutional resistance. In some cases, the host organization can act like it "just wants the money" for replication operations, knows better and really is not interested in the replication model. When all goes well, the advantage to integrating just some components can be the creation of a new hybrid that is a synthesis of the best of the model and best of the host. 6. Strategic Communications Training is An Essential Component of Capacity Building and Replication Few grassroots nonprofits are skilled in media and communications. This is not surprising -- because few can afford a communications director and communications office. Not many grassroots nonprofit executive directors have had the time to think through this part of their organization's mission. Yet these groups typically undertake advocacy, and organizing requires communication. When groups achieve success in their programs, communicating that success can bring recognition, attract new trustees and generate more interest by funders. Increased funding can be used to improve management, financial management and staff development. The funding can finance new computers and a new director for fundraising. Most of these grassroots organizations oppose policies like tax breaks for the rich and prison building for the poor. They have well thought out alternative policy frameworks that make more sense. Yet they have not been trained to use the media to articulate their frameworks and positions. For the most part, those who support a frame of tax breaks for the rich and prison building for the poor have been trained; as a consequence, the latter have increased the likelihood that their ideas will prevail. In response, the Eisenhower Foundation has trained over the past ten years several cohorts of inner-city nonprofit organization executive directors and other senior staff at the Foundation's strategic communications school. The school runs over four days. The first two days cover how to develop a strategic communications and advocacy campaign that identifies the message, the message senders and the target audiences. Also covered are basics like how to hold a press conference, write a press release, develop a press kit, "pitch" a story, write an "op ed," write a letter to the editor, and create public service advertising. Over the remaining two days, the Foundation sets up a television camera and television studio. Training is led by the Foundation's director of communications. Each participant must present the mission of her or his organization in one or two minutes in front of the camera. Then each must undertake an interview with reporters who act in a friendly and receptive manner. Next, each must undertake a hostile interview on what works and what does not. Training concludes with groups of participants undergoing press conferences with our trainers acting as aggressive and sometimes offensive reporters. Each round of this training is videotaped, replayed and critiqued in front of the other participants. Grassroots nonprofit participants learn electronic media lessons that allow them to control the agenda and effectively communicate their messages. Advocates for programs that work at the grassroots learn how not to respond to loaded questions and to promote their views within a framework in which they feel comfortable. Good television can, we teach, promote consensus building. We have found that the lessons from television training also apply to talk radio and public speaking. Progress often is dramatic. Increased media acumen enhances leadership skills. At the end of training sessions, many grassroots leaders admit that, prior to training, they had little experience in using media as a tool for capacity building, replication and advocacy. Many immediately put into practice lessons learned. For example, one organization effectively used newfound media skills to generate publicity after a major investor in its inner city health program terminated funding. The publicity resulted in raising enough funds to surpass the amount that was cut. Many foundations are wary of funding communications. Yet there is a need to fully develop a strategic communications plan for each nonprofit organization, implement it over two or three years and measure for concrete, ultimate outcomes. One such outcome might be more funds received as a result of publicity. Another might be success in changing local television news to include more stories on what works and fewer stories about violence and demonized minority youth. Conclusions In 1968, after America's big city riots, the Kerner Riot Commission (National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders, 1968) proposed that we replicate what works to " a scale equal to the dimensions of the problem." Today, the most creative funding for capacity building and replication comes from a few traditional foundations as well as from new venture philanthropy funds generated by dot.com fortunes. Yet the resources from the leaders are minuscule. Few institutions dare to discuss replication to scale. Over the last year, three solid new national evaluations have documented the success of well-run preschool for disadvantaged children. Yet there is no serious attempt to secure the approximately $8B more per year needed nationally to provide Head Start preschool to all the poor children who qualify (Curtis 2001). What are we to do? The philanthropic world can start not only with the expanded funding we have concluded is necessary, but also with encouragement to nonprofits to reorganize their ways of doing business. Figure 2 shows the kind of organization that we believe is desirable for national and larger local nonprofits working in child and youth development, public school innovation, job training and placement, advocacy, crime and violence prevention, drug prevention, and community-police partnership. Figure 2

To address all that we have proposed, national nonprofit organizations should, we believe, retain more traditional capacities -- including policy research and evaluation, fundraising and technical assistance. But, especially when it comes to technical assistance on communicating what works, such national nonprofits should create more sophisticated offices for marketing and communications, leveraging change at state and local levels, and mobilizing grassroots constituencies that can push for more of what works. There are some national nonprofits with our view of what works that already are organized in this way, but far too few. For their part, funders that want to expand support for investments in human capital that work should, we believe, provide sustained and unrestricted support for all of the activities shown in Figure 2, not intermittent and categorical support for some. Such funding will make it much easier than at present for national nonprofits with our perspective to carry out a broad, democratizing vision of what works that is integrated with specific policy and program initiatives. More funding to national nonprofits modeled after Figure 2 also will make it easier than at present to pursue structural reforms that have the potential to change the substance of national policy and the rules of the game far into the future. Adequately funded national and local nonprofits modeled after Figure 2 can join to push the public sector to incorporate line item commitments to capacity building in all grants and to become more sophisticated in replicating what works. Ultimately, we need a grassroots movement led by nonprofits that are organized along the lines of Figure 2. The movement should communicate to taxpayers and voters that we do know what works and have the knowledge at hand to build capacity and replicate what works to scale. Such a movement must refocus the national debate. The obstacle to expanding capacity and replicating to scale for the truly disadvantaged is not lack of knowledge. It is lack of political will by public and private leaders to release the resources of the richest nation in history. References Alexander, Bill. (1999). "On and Off the Wagon: America's Promise At Two." Youth Today, July/August. Belluck, Pam. (1997). "Urban Volunteers Strain to Reach Fragile Lives," New York Times, April 27, p. A1. Bennett, James. (1997). "At Volunteerism Rally, Leaders Paint Walls and a Picture of Need," New York Times, April 27, p. A1. Curtis, Lynn A. Lessons from the Street: Capacity Building and Replication (2000). Washington, DC: Milton S. Eisenhower Foundation. This report is posted in its entirety at www.eisenhowerfoundation.org. Curtis, Lynn A. Unequal Protection: Corrupted Democracy. (2001). Washington, DC: Milton S. Eisenhower Foundation. This report is posted in its entirety at www.eisenhowerfoundation.org. Mosle, Sara. (2000). "The Vanity of Volunteerism." New York Times Magazine, July 2, p. 22. National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders. (1968). Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. New York Times Editorial. (1995). "A Youth Program That Worked." New York Times, March 20, p. A18. [ Back ]

|