|

Reform of Tax and Child Poverty Policy In the 1990s, poverty decreased. But those left behind were poorer still. Today about eighteen percent of all children aged five and under live in poverty in the world's only superpower. This is much higher than in any other industrialized democracy. If all the 13.5 million poor children in America were gathered in one place, they would form a city bigger than New York. About twelve percent of all Americans live in poverty -- roughly twice as high as any other industrialized nation.1 Why should a country this rich have any poverty? What can be done?

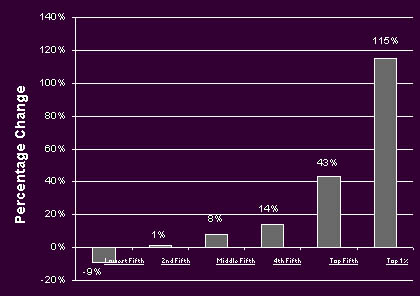

Question Economic Policy No plan to reduce and eliminate child poverty has yet been proposed by the Administration or a majority in Congress. However, supply side economics are being invoked, as in the 1980s. Supply side economics essentially are tax breaks disproportionately for the rich. Benefits are said to trickle down to the poor. Yet the record is crystal clear that supply side economics have never worked for the poor. When supply side economics were tried, the rich got richer and the poor got poorer over the decade of the 1980s, according to conservative author Kevin Phillips and many others. Over the 1980s, the working class also got poorer; the middle class stayed about the same, so it lost ground to the rich. In 1980, the income of the top one percent of earners in America was equal to the income of the bottom twenty percent. Today, the income of the top one percent is equal to the income of the bottom thirty-eight percent. The top 2.7 million people in America today have a total income equal to that of the bottom one hundred million.2 Figure 3 shows the increase in income inequality from 1977 to 1999. Figure 3 Disparities in wealth in America are even greater. The median wealth of nonwhite American citizens actually fell during the 1980s. The average level of wealth of an African-American family in America today is about one-tenth of an average white family. Three white American men now have combined wealth that exceeds the total Gross National Product of forty-three countries. Wealth inequality is much worse in the United States than in countries traditionally thought of as "class ridden," like the United Kingdom.3 The increase in income and wealth inequality has been unprecedented. The only comparable period in America in the twentieth century was 1922-1929, before the Great Depression. From the perspective of racial differences, net worth is a powerful, related measure. Net worth equals the sum of everything you own less your total outstanding debt:4

Inequality between CEOs and workers also has increased dramatically. In 1980, before supply side economics, the average corporate CEO received forty-two times as much as the average factory worker. Today, the average corporate CEO receives 419 times as much as the average worker.5 As with poverty, no macroeconomic plan has been proposed by a majority in Congress or the Administration to reduce income, wealth, equity or CEO-worker, inequality. The budget surplus over the next decade currently is estimated at about $5.6 trillion (although such projections can quickly change with different future economic scenarios). The surplus amount outside of Social Security is about $3.1 trillion over the next decade. Of this amount, the Administration's tax cut took $1.3 trillion. There also are proposals to increase military spending (with a new star wars plan included), increase spending on other priorities not associated with the truly disadvantaged, increase corporate welfare and pay off a substantial amount of the national debt by the end of the decade.6 The $1.3 trillion tax cut further increases income and racial inequality. It disproportionately favors the rich. The top one percent of taxpayers pay twenty-one percent of all federal taxes, but they receive forty-three percent of the Administration's tax cut -- more than twice their share. In our view, this money for the rich should have been saved to pay for the huge increase in spending needed combat to terrorism. As in the 1980s, supply side tax cuts for the rich are said to be the best way to stimulate the economy and trickle down benefits to the rest of the population.7 What was the result in the 1980s? Increased poverty, increased inequality and enormous deficits that spiraled out of control and put the economy in peril. How were those deficits reversed? By the opposite of supply side economics -- a 1993 tax increase for the highest income brackets. What was the result? In spite of the initial protests of supply siders, the nation experienced the most sustained expansion in its history, which changed the deficits of the 1980s and 1990s into the unprecedented surpluses that supply siders now are seeking to "get rid of " through tax cuts.8 The 1990s achieved the interim goals of the Humphrey-Hawkins Act of the late 1960s -- a four percent unemployment rate and an inflation rate of less than three percent -- something supply siders had said was impossible.9 As part of the $1.3 trillion tax cut, the estate tax was repealed. This was done in spite of a petition to Congress by some 120 wealthy Americans, including philanthropist George Soros and the father of William H. Gates, that (in Mr. Gates, Sr.'s words) "repealing the estate tax would enrich the heirs of America's millionaires and billionaires while hurting families who struggle to make ends meet." Added Warren Buffet, the Omaha investor who ranks fourth on the Forbes list of the richest Americans, repealing the estate tax "would be a terrible mistake," the equivalent of "choosing the 2020 Olympic team by picking the eldest sons of the gold metal winners in the 2000 Olympics.... Without the estate tax, you in effect will have an aristocracy of wealth, which means you pass down the ability to command the resources of the nation based on heredity rather than merit."10 As William Greider concludes, "[I]n the real world, economic stimulus requires steeply progressive tax cuts -- putting money in the hands of people who will promptly spend it. That means quick rate cuts or temporary tax credits that skip over the upper brackets for a change and deliver the money to the bottom half of the income ladder." It also means a refundable children's tax credit of $1000 per child -- which some believe would do more to reduce poverty than any single initiative.11 In addition, only a small part of the originally estimated ten year budget surplus is expected in the Administration's current term. Most of the surplus is projected for later -- and estimates of the surplus are shrinking day-by-day. As columnist David Broder has concluded, "The prudent thing to do, as many have suggested, is to enact a much smaller tax cut now, one that can be paid for out of existing surpluses, not projected or dreamed-of distant fortunes, and then watch what happens in this uncertain economy." Any such smaller tax cut should be limited to four years and not tie the hands of future Administrations.12 In reality, the $1.3 trillion tax cut will be financed by tapping revenues generated by Medicare, jeopardizing the future solvency of Social Security and cutting domestic spending programs.13 The revenue loss will make it impossible for Congress to set aside in a "lock box" nearly $3 trillion in surpluses projected to be generated by Social Security and Medicare over the next ten years.14 As in the 1980s, tax cuts, debt reduction and military spending are being used as strategies for "getting rid of the surplus" -- so it can't be used, in part, for example, to invest to scale in proven solutions for the poor, workers and the middle class. Nor did this policy anticipate the greatly increased spending against terrorism that the government belatedly is recognizing is thirty years overdue.15 The strategy of "getting rid of the surplus" so "big spenders" can't touch it is based on hypocrisy and ideology. The hypocrisy is that there is big spending going on -- spending the surplus on the rich, corporate welfare and the military. The ideology is that all spending is wasteful -- unless it is spending on the rich, corporate welfare, the military and the debt. But the truth is that some spending is wasteful and some is cost-effective, based on scientific evaluations. That is why we advocate for an evaluation-based policy of cutting what doesn't work and replicating to scale what does work for the truly disadvantaged. Few in Washington seem to understand the difference between policy based on political ideology and policy based on scientific evaluation. Or, if they do understand, they allow their understanding to be overridden by one dollar, one vote politicking. The strategy of "getting rid of" spending on items other than the rich, corporations, the military and the debt also runs counter to national public opinion polls. The polls show that, while Americans are receptive to the idea of paying lower taxes, they don't necessarily want to do so at the expense of programs and priorities that they cherish.16 In sum, debates in Washington on the surplus and tax cuts are stunningly devoid of any serious plan to replicate what works to scale for the truly disadvantaged. By contrast, the Eisenhower Foundation's education, training, jobs, racial justice and criminal justice plan costs about $50 billion to $60 billion per year over the next decade.17 Question Enterprise Zones One form of trickle down supply side economics is the enterprise zone -- the notion that, if we give sufficient tax breaks to corporations, they will move into devastated places like South Central Los Angeles and employ minority youth. A new enterprise zone tax break package was approved by Congress and signed by the President in Fall, 2000. However, the failure of enterprise zones in South Central Los Angeles and elsewhere has been carefully documented -- for example, by the Urban Institute in Washington, DC and by the United States General Accounting Office. The failure also is well recorded in publications targeted at businesspeople and investors, like the Economist and Business Week. Among other reasons given by corporations for why they would not move back and employ inner-city youth was the opinion that youth were not adequately trained.18 Hence, the need for job training programs for the hardest to employ at a time when the fashion is "work first." Support Community Development Corporations and Banking. Nonprofit community development corporations have worked better for the truly disadvantaged and the inner city than enterprise zones. The movement began decades ago with ten community development corporations. Now there are over 2,000. One good example is the New Community Corporation in the Central Ward of Newark -- founded in the ashes of the 1960s riot there by Monsignor William Linder, who has received a MacArthur Foundation genius award. The New Community Corporation has generated thousands of economic development jobs and associated services jobs in the Central Ward. One of its affiliates also owns the only Pathmark Supermarket in the Central Ward. Income streams from this for-profit business help finance nonprofit operations.19 Community development corporations have created revivals over the long run in a number of previously devastated neighborhoods -- for example in Kansas City, New York, Chicago and Cleveland.20 Federal appropriations for housing the poor were reduced by over eighty percent in the 1980s, at the same time that the number of prison cells quadrupled.21 One of the few potentially constructive housing and development trends for the poor over the last twenty years has been that, with funds available, the federal government has channeled dollars through two national nonprofit intermediaries -- the Enterprise Foundation (created by for-profit developer James Rouse) and the Local Initiatives Support Corporation (LISC, created by the Ford Foundation). In turn, these national nonprofit intermediaries targeted federal funds to local community development corporations, leveraged public dollars against private dollars, helped private investors find opportunities to invest in community development programs, provided technical assistance and managed the funds. This process now is the leading mechanism in the nation to rehabilitate and otherwise provide housing for the poor.22 However, the two intermediaries still impact just a small proportion of all neighborhoods in need. They don't adequately provide housing for families with incomes below $20,000. Nationally syndicated columnist Neal Peirce concludes that either the Enterprise Foundation and LISC should be significantly expanded or "a whole new set of intermediaries should be created, to get up to the scale we need to rebuild decaying communities rapidly and well."23 Some in the community development movement argue for the latter option to avoid excessive accumulation of power by any single intermediary. The capital for community development corporations can be secured via community-based banking. Here the model is the South Shore Bank in Chicago. Many banks do not bother with branches in the inner city. When they do, typically a bank will use the savings of inner-city residents to make investments outside of the neighborhood. South Shore does just the opposite. It uses the savings of the poor to reinvest in the inner-city neighborhoods where the poor live. And South Shore still makes a profit. However, the community banking movement remains in its infancy. We believe it needs to be taken to scale through a new National Community Development Bank.24 It is past time for a fresh look at housing, community development and community banking. Starting from scratch, what would be the best policy? How many new national intermediaries should be added? How can the Enterprise Foundation, LISC and new national intermediaries better provide housing for families with incomes below $20,000? What expanded role can Habitat for Humanity play? How should a National Community Development Bank work? How can grassroots community development corporations be improved in quality and expanded in number? How can community development corporations incorporate components that invest in human capital and encourage advocacy? What new mechanisms of nonprofit leadership development can be created for young persons in the inner city? How can community development corporations better integrate the goals of YouthBuild USA, which trains inner city youth to repair and rehabilitate low income housing -- and to become leaders? Should grassroots nonprofits give priority to housing production? Or should for-profit organizations produce housing while nonprofit community development corporations concentrate on allocating and managing the housing? What alternatives to the present low income tax credit financing mechanism might be considered? How can we begin to return to a commitment to housing for all who need it, as set forth in the original housing act of the 1930s? We need to create private sector and public sector commissions to debate such questions. Private sector advocates need to agree on a new policy, even though Washington initially will oppose it. At this point in time, there appears to be little interest by a majority in Congress and by the Administration in starting from scratch, answering the big questions, creating commissions or expanding and refining the community development corporation and community banking movements. Some in Congress want to further weaken the Community Reinvestment Act, which has greatly helped community development corporations secure capital.25 Reduce Unemployment and Underemployment Pundits in Washington, DC talk of an unemployment rate of around 4.2 percent. Yet the Economic Policy Institute in Washington DC, estimates that the rate of underemployment is between seven and eight percent -- when one takes into account official unemployment rates, the number of people who have stopped trying to find jobs and who therefore are not counted, and persons working part-time who want to work full time. (Much of this underemployment is associated with temporary jobs that offer few, if any, benefits.) In addition, the United States Department of Labor has concluded, "The employment rate for out-of-school youth in high-poverty areas typically is less than 50 percent." The Center for Community Change in Washington, DC has estimated that the real "jobs gap" is over four million jobs nationally. Of that, perhaps half of the jobs needed are in the inner city.26 There is no Administration plan and no plan among a majority in Congress to eliminate the jobs gap and to reduce underemployment. Reform Job Training and "Welfare Reform" Another component of 1980s trickle down supply side economics was the Job Training Partnership Act (JTPA). We know from evaluations by Mathematica Inc. commissioned by the United States Department of Labor that JTPA failed for high school dropouts. Grossly underfunded, JTPA, in spite of its name, had little training. It was a failed "work soon" or "work first" program.27 "Work first" is the cornerstone of the "welfare reform" that was carried out in the last decade. By "welfare reform" we mean waivers on welfare regulations given by the federal government to the states in the early 1990s and the federal Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act of 1996. The 1996 federal legislation created block grants that virtually delegated to the states responsibility for creating a new system. In signing the legislation in 1996, the President quoted Robert F. Kennedy: "Work is the meaning of what this country is all about. We need it as individuals. We need it in our fellow citizens. And we need it as a society and as a people." However, as Peter Edelman has written, the President "highjacked" and "twisted" Robert Kennedy's words and meaning. Kennedy's vision was a national investment to insure that the poor got sufficient education, training and jobs to provide for themselves and especially for their children. Instead, the 1996 legislation, in Edelman's words, "invited states to order people to work or else, even if there are no jobs, and with no regard for what happens to them and their children."28 Many evaluations are underway that assess the impact of the waivers to states in the early 1990s and the impact of the 1996 federal legislation. What are the main findings to date? There is little unequivocal proof that "welfare reform" has had a great impact, compared to the impact of the booming economy. How do you measure success? Proponents of "welfare reform" claim that the measure of success is reduction in welfare rolls. And in fact welfare case loads were cut in half between 1994 and 1999. However, the current consensus is that only between about fifteen to thirty percent of the drop is attributable to "welfare reform." Most of the drop is attributable to the booming economy, according to the studies.29 The robust economy of the 1990s was set in motion by the tax increase in 1993 -- bitterly opposed by supply side advocates of tax cuts for the rich. "Welfare" originally was designed as a strategy against child poverty. So the real measure of success is less child poverty, not reduced welfare rolls. The rate of child poverty has dropped in recent years. However, there is no evaluation consensus that "welfare reform," rather than the booming economy, is primarily responsible.30 Where do existing evaluations leave the nation in the wake of the 1996 federal legislation? The official poverty rate for children five and under is eighteen percent. For children of color, one of three is poor, based on the official definition of poverty. These poverty rates are higher today than in all of the 1970s. The official rates are much higher than for all other industrialized nations.31 Yet the official rates underestimate poverty. Since the official poverty line was established in the 1960s, the cost of living for the poor has risen much faster than the rate of inflation, especially for housing. As the Economic Policy Institute has documented, the current poverty definition insufficiently measures the basic income needs of a working family. More accurate measures are needed -- like those recommended by the Panel on Poverty and Family Assistance of the National Research Council. For example, except when one parent stays home with a child, the Panel concludes that minimally acceptable budgets for working families must incorporate child care costs. "Given the variation and importance of quality care for child development, the amount budgeted for child care must be high enough to ensure that working families can afford reliable care of decent quality." The Economic Policy Institute estimates that, just to meet basic needs and achieve a safe and decent standard of living, a family of four in Baltimore requires an annual income of $34,732.32 The 1996 "welfare reform" legislation fell far short of ensuring such standards. The legislation did little to provide poor people with child care, job training, education, health care and transportation to and from work -- the kinds of support services that are essential to people leaving welfare for the job market. The 1996 legislation also restricted the availability of food stamps and reduced benefits for legal immigrants.33 Because of the latitude given by the 1996 state block grants, many states have adopted harsh policies -- including short time limits to remain on welfare, as well as extensive terminations. As many as forty percent of women who left welfare have not found jobs, according to studies conducted by many states and by research organizations like the Urban Institute and the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. Many women secured dead-ended jobs and are still living below the poverty line. Many found jobs -- but part time jobs, not the full time jobs they needed to support their families. Some who have found jobs have not been given access to health care. Many who found jobs have children who do not receive adequate day care. The restrictions on food stamp eligibility have caused many hardships. The profit making companies that received lucrative contracts to find jobs for former welfare recipients have not performed particularly well, yet there is very little discussion of their shortcomings by apologists for the 1996 legislation, politicians and the media.34 Today, about 2.5 million people still are on the welfare rolls. They are in especially difficult circumstances. They tend to have less education, fewer job skills, less work experience and more personal problems than those who have gotten jobs. It is these people who will be hurt, in particular, when they face the five year lifetime limit on federally funded assistance imposed by the 1996 legislation. It is these people who will be hurt all the more if and when the nation experiences a recession.35 Under the 1996 legislation, if a welfare recipient gets a job and then loses it, many states deny further support. They simply tell the individual to find another job. As a result, there now are many women who are neither working nor on welfare. The number is about one million -- plus their two million children. These three million people have "disappeared" -- they are not identified as former welfare recipients in record keeping by the states. The only way these people really "appear" is when we look at poverty statistics. While overall poverty has gone down (not, as we have seen, necessarily because of "welfare reform"), the people left behind in poverty are even more poor. Some of these are the disappeared mothers and their children. Many of the mothers have incomes below half the official poverty line -- $6,750 for a family of three. These mothers are more poor than before because they have lost welfare payments, lost food stamps and do not have jobs.36 The U. S. Conference of Mayors has found that requests for emergency food increased by seventeen percent in 2000. Two-thirds of the people requesting assistance were families with children. Demand for emergency shelter increased fifteen percent in 2000, and of those thirty-six percent were families with children. The leading causes of these increases were low-paying jobs, lack of affordable housing, unemployment, other employment-related issues and poverty.37 In spite of the needs of poorer families still on welfare and the needs of the families that have "disappeared," many state governments are not spending the federal funds intended to help them transition into work or take care of their children. Forty-six states and the District of Columbia have failed to use more than $8 billion authorized by Congress for child care, transportation, education, job training and other efforts to help support low-wage workers and struggling families, according to a report by the National Campaign for Jobs and Income Support issued in February, 2001. Fourteen states actually have increased their surplus of unspent "welfare reform" funds since 1999. Some states -- Connecticut, Virginia, Texas, Wisconsin and Michigan in particular -- are abusing the flexibility of their "welfare reform" funds to pay for tax cuts and shortfalls in other areas of their budgets.38 Given that lack of real job training is one of the failures of the 1996 legislation, it is important to be clear that there are a number of already proven job training and retention models. They can be replicated -- for welfare clients as well as for out-of-school youth (with many persons in both categories). Just a few examples of job training and retention models that work, based on careful evaluations, include the Argus Community in the South Bronx (where some trainees learn to be drug counselors), Capital Commitment in Washington, DC (where trainees learn to repair telecommunications equipment), the Job Corps nationally (which was most recently evaluated positively by Mathematica Policy Research, Inc.) and YouthBuild USA (which trains drop outs to rehabilitate inner city housing and has been evaluated as successful by a team from the Kennedy School at Harvard University.)39 However, in spite of the availability of proven job training models, there is, incomprehensibly, no national system for replicating them and providing technical assistance. As Paul Grogan and Tony Proscio point out in Comeback Cities:40 The American system of local job-training programs operated by the public sector and nonprofit organizations is largely a disgrace -- resembling today what the community development system looked like twenty years ago. There is a sprinkling of exemplary local programs in a desert of waste and ineffectuality. Across broad swaths of the urban landscape, local employment and training systems are operated as political fiefdoms or social-service programs. There are no organized mechanisms for large-scale private capital or employer involvement, or for elevating and spreading the best approaches, or for driving out the purely political operations. The Eisenhower Foundation has proposed nonprofit intermediaries that supply high quality technical assistance to local job training for the poor, leverage public against private job training funds, replicate proven models and link poverty reduction to economic development (a link that, astoundingly, the federal government does not currently make).41 Grogan and Proscio appear to endorse this strategy. In light of existing evaluations and current knowledge, what is the best course in 2002, when the 1996 "welfare reform" legislation is up for reauthorization? Scrap the old legislation and start over. Instead of political spin that claims to measure success in terms of reduced caseloads, we need to be honest -- and measure success in terms of the original goal: reduction in child poverty. Poverty should be defined following the recommendations of the National Research Panel (above). Local "welfare reform" programs that reduce poverty, so defined, should be rewarded. We ought to require local "welfare reform" programs to combine job training, quality job creation, job placement, job retention, health insurance, high quality child care and high quality transportation services. We should encourage replication of "welfare reform" and job training models that work, based on scientific evaluations, and explicitly link these investments to replication of successful inner city public school reforms. Federal "welfare reform" dollars should not be channeled to localities via the states, but via national and regional nonprofit intermediaries. We need to create national nonprofit intermediary organizations that co-target existing federal job training and economic development initiatives to places of great need; expand the number and quality of grassroots, nonprofit community development corporations that create jobs; and fund these priorities from the federal budget surplus and the state "welfare reform" surpluses. The nation must acknowledge how conventional macroeconomic policy does not target structural unemployment and does not create enough jobs to eliminate the current gap of over four million urban and rural jobs needed. We ought to build in economic stabilizers that provide buffers in times of economic recession. We need to define a baseline of support below which a local "welfare reform" program cannot fall and allow more flexibility in time limits. We must create more local accountability and abolish the most punitive present state "welfare reform" policies.42 A majority in Congress and the Administration are unlikely to accept our plan. The Secretary of Health and Human Services has been criticized for focusing on caseload reduction rather than child poverty reduction when he was a governor, and for creating massive caseload reductions "by simply losing track of former recipients or dissolving them in a sea of working poor."43 In addition:44 The number of children placed in foster care has risen rapidly in Wisconsin, by 32 percent in the past decade, and by 51 percent in Milwaukee, where the welfare population is concentrated. Reports of child abuse and neglect are rising, and so are the reported incidents of domestic violence and juvenile arrests. But by far the most Dickensian development is the rise in infant deaths. The national downward trend in mortality rates for Black and Hispanic infants has been reversed in Wisconsin. The mortality rate of black newborns, once lower than other Midwestern states, is now the highest in the region. The bottom line is that Wisconsin's welfare cutbacks have left people working more but poorer, and substantial numbers of these people are desperately poor. However, the Secretary of Health and Human Services has argued, "You can't expect welfare mothers to go to work unless they have child care. They've got to have health insurance, transportation and training. All costs money."45 We agree. This position is supported in a recent evaluation by the Manpower Development Research Corporation (MDRC). In six states with a total of eleven programs, MDRC found that school performance by children in welfare families improved when family income increased through mandatory work combined with extra money or benefits like child care subsidies. Importantly, the evaluation concluded what many have argued for years -- that "increasing employment alone does not appear sufficient to foster healthy development of children."46 Notes and Sources Washington Post, "The Campaign's Missing Issues," Washington Post, October 10, 2000; New York Times, "A Metropolis of Poor Children," New York Times, August 20, 2000, p. A30; Doug Henwood, "The Nation Indicators," Nation, March 29, 1999, p. 10; Alan Wolfe, "The New Politics of Inequality," New York Times, September 22, 1999, p. A27; Kenneth Bredemeier, "Widening Gap Found Between Area's Rich, Poor" Washington Post, November 29, 2000, p. E1. [Back] Kevin Phillips, The Politics of Rich and Poor (New York: Random House, 1990); Jason DeParle, "Richer Rich, Poorer Poor, and a Fatter Green Book, "New York Times, May 26, 1991; Alan Curtis, Family, Employment and Reconstruction (Milwaukee: Family Service America, 1995); U.S. Census, Historical Poverty Tables (Washington, DC: U.S. Census, 1997); Children's Defense Fund, The State of America's Children (Washington, DC: Children's Defense Fund, 1994); Felicity Baringer, "Rich-Poor Gulf Widens Among Blacks, New York Times, Sept. 25, 1992; and Alan Wolfe, "The New Politics of Inequality," New York Times, September 22, 1999, p. A27. [Back] Keith Bradsher, Gap in Wealth in U.S. Called Widest in West," Dalton Conley, "The Black-White Wealth Gap," Nation, March 26, 2001, p. 20. [Back] Alan Wolfe, "The New Politics of Inequality," New York Times, September 22, 1999, p. A27. [Back] Dan Morgan and Kathleen Day, " Early Wins Embolden Lobbyists for Business," Washington Post, March 11, 2001, p. A1; Mike Allen, "Bush May Budge to Get a Tax Cut, "Washington Post, March 10, 2001, p. A1; New York Times, "Voting First, Debating Later, "New York Times, March 11, 2001, PWK 14; New York Times, "Countering the Bush Tax Plan," New York Times, March 4, 2000, PWK 14; Robin Toner, "Cutting a Rightward Path", New York Times, March 4, 2001, PWK 1. [Back] New York Times, "Are Democrats Ready on Taxes?" New York Times, February 6, 2001, p. A33; Jeffrey Rosen, "Bus Stop; The Lost Promise of School Integration," New York Times, April 2, 2000. [Back] Alice M. Rivlin, "Why Fight the Surplus?" Washington Post, January 30, 2001, p. A27; New York Times, "An Appraisal: Bill Clinton's Mixed Legacy," New York Times, January 14, 2001, p. WK 16; Richard W. Stevenson, "The High Stakes of Spending the Surplus," New York Times, News of the Week in Review, January 7, 2001; New York Times, "Interpreting Mr. Greenspan," January 26, 2001, New York Times, p. A22; Joan M. Berry, "Greenspan Supports and Tax Cut," Washington Post, January 26, 2001. p. A1; Richard W. Stevenson, "Bush's Proposal to Cut Taxes is Swiftly Introduced in Senate," New York Times, January 23, 2001, p. A15. [Back] Jeff Faux, "What Kind of America Do We Want?" in Robert L. Borosage and Roger Hickey, editors, The Next Agenda (Boulder and Oxford: Westview Press, 2001, p. 31). [Back] David Cay Johnson, "Dozens of Rich Americans Join in Fight to Retain the Estate Tax," New York Times, February 14, 2000. [Back] William Greider, "Treasury Nominee O'Neil: Just in Time for Trouble," Nation, January 29, 2001, p. 13; New York Times, "The Fed Moves First," New York Times, January 4, 2001, p. A.24. [Back] David S. Broder, "A Shaky Budget," Washington Post, March 2, 2001, p. A25; E. J. Dionne Jr., "We'll Get Over It If You Get Off Your High Horse," Washington Post, January 28, 2001, p. B1. [Back] New York Times, "The Return of Fuzzy Math," New York Times, March 1, 2000, p. A26. [Back] New York Times, "Voting First, Debating Later, "New York Times, March 11, 2001, PWK 14; Robin Toner, Cutting a Rightward Path", New York Times, March 4, 2001, PWK 1. [Back] Alice M. Rivlin, "Why Fight the Surplus?" Washington Post, January 30, 2001, p. A27. [Back] John Lancaster, "Tax Cut Ambivalence: Nice, But A Priority?" Washington Post, February 15, 2000, p. A14. [Back] See A Budget for the Truely Disadvantaged and the Inner City. [Back] Urban Institute, Confronting the Nation's Urban Crisis: From Watts (1965) to South Central Los Angeles (Washington, DC; Urban Institute, 1992); William J. Cunningham, "Enterprise Zones," Testimony before the Committee on Select Revenue Measures, Committee on Ways and Means, United States House of Representatives, July 11, 1991; Tom Furlong, "Enterprise Zone in L.A. Fraught with Problems," Los Angeles Times, May 19, 1992; "Reinventing America," Business Week, January 19, 1993; "Not So EZ," Economist, January 28, 1989. [Back] Alan Curtis and Fred R. Harris, The Millennium Breach (Washington, DC: The Milton S. Eisenhower Foundation, 1998, Chapter 6). The publication is posted in its entirety under Publications. [Back] Paul S. Grogan and Tony Proscio, Comeback Cities (Boulder and Oxford: Westview Press, 2000). [Back] Robert Suro, "More Is Spent on New Prisons Than Colleges," Washington Post, February 24, 1997; Beatrix Hamburg, "President's Report," Annual Report, 1996 (New York: William T. Grant Foundation, 1997). [Back] Paul S. Grogan and Tony Proscio, Comeback Cities (Boulder and Oxford: Westview Press, 2000). [Back] Neil Peirce, Powerful New Allies for the Poorest Neighborhoods," Times-Picayune, April 4, 1994. For policies like community development and community banking, we define success in terms of the cost effectiveness of jobs and housing created for the poor -- along with the degree to which the program reduces inequality. [Back] For South Shore Bank, see: Michael Quint. "This Bank Can Turn a Profit and Follow a Social Agenda." New York Times, May 24, 1992. For a National Community Development Bank see: Alan Curtis and Fred R. Harris, The Millennium Breach (Washington, DC: Milton S. Eisenhower Foundation, 1998, Chapter 6). The latter report is posted in its entirety under Publications. [Back] Bob Herbert, "Fragile Victories," New York Times, December 28, 2000, p. A23; and Colbert I. King, "After Chavez," Washington Post, January 15, 2000, p. A21. [Back] Center for Community Change, Newsletter (Issue 19, Fall 1997); Federal Register, Volume 64, Number 105, Wednesday June 2, 1999, p. 29672; Alan Okagaki, Developing a Public Policy Agenda on Jobs (Washington, D.C.: Center for Community Change, 1997); Jerry Jones, Federal Revenue Policies That Work: A Blueprint for Job Creation to Support Welfare Reform (Washington, D.C.: Center for Community Change, 1997); William Julius Wilson, When Work Disappears: The World of the New Urban Poor (New York: Knopf, 1996); and Lawrence Mishel, Jared Bernstein and John Schmitt, The State for Working America (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2000). [Back] Federal Register, Job Training Partnership Act: Youth Pilot Projects. Volume 59, No. 71, April, 13, 1994. [Back] Peter Edelman, Searching for America's Heart (Boston and New York: Houghton Mifflin Company, 2001, pp. 1-2). [Back] Jared Bernstein, Chauna Brocht and Maggie Spade-Aguilar, How Much is Enough, Basic Family Budgets for Working Families (Washington, DC: Economic Policy Institute, 2000). [Back] Interview with Jared Bernstein, Economic Policy Institute, Washington, DC, January 19, 2001. [Back] Peter Edelman, Searching for America's Heart (Boston and New York: Houghton Mifflin Company, 2001), pp. 10, 14. [Back] Peter Edelman, Searching for America's Heart (Boston and New York: Houghton Mifflin Company, 2001, pp. 10, 14; Jared Bernstein, Chauna Brocht and Maggie Spade-Aguilar, How Much is Enough, Basic Family Budgets for Working Families (Washington, DC: Economic Policy Institute, 2000), pp. 1-3. [Back] Pablo Eisenberg, "Jobs Coalition: A Chance for Foundations to Walk Their Talk," Chronicle of Philanthropy, December 14, 2000. [Back] Peter Edelman, Searching for America's Heart (Boston and New York: Houghton Mifflin Company, 2001, Chapter 5). [Back] Peter Edelman, Searching for America's Heart (Boston and New York: Houghton Mifflin Company, 2001, pp. 144-145). [Back] Peter Edelman, Searching for America's Heart (Boston and New York: Houghton Mifflin Company, 2001, p.146). [Back] Jim Wallis, "A Church-State Priority," Washington Post, January 8, 2001. [Back] National Campaign for Jobs and Income Support, Poverty Amidst Plenty 2001: Unspent TANF Funds and Persistent Poverty (Washington, DC: National Campaign for Jobs and Income Support, February 2001). [Back] For evaluation details on Argus, see Milton S. Eisenhower, Replication of the South Bronx Learning for Living Center (Washington, DC: Milton S. Eisenhower Foundation: 2001). This publication is posted in its entirety under Publications. For the other models, see Alan Curtis and Fred R. Harris, The Millennium Breach, (Washington, DC: Milton S. Eisenhower Foundation, 1998). This publication also is posted in its entirety under Publications. Also see United States Department of Labor, National Job Corps Study: The Short Term Impact on Participants Employment and Related Outcomes (Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Labor, 2000). [Back] Paul Grogan and Tony Proscio, Comeback Cities (Boulder and Oxford: Westview Press, 2000). [Back] Alan Curtis and Fred R. Harris, The Millennium Breach (Washington, DC: Milton S. Eisenhower Foundation, 1998). This report is posted in its entirety under Publications. [Back] Peter Edelman, Searching for America's Heart (Boston and New York: Houghton Mifflin Company, 2001, p. 176). [Back] Joel Rogers, "The Man From Elroy," Nation, January 29, 2000, p. 15. [Back] Frances Fox Piven, "Thompson's Easy Ride," Nation, February 26, 2001, p. 4. [Back] Joel Rogers, "The Man From Elroy," Nation, January 29, 2000. [Back] Robert Pear, "Gains Reported For Children of Welfare to Work Families," New York Times, January 23, 2001, p. A12. [Back] |