|

A Fair Economic Deal How can we secure new voting majorities to pass a national policy that replicates what works for the truly disadvantaged to a scale equal to the dimensions of the problem? We can do so by creating a broader framework that is attractive to workers and the middle class, as well as to the poor. We call this framework a Fair Economic Deal. To bring together the middle class, workers and the poor, a Fair Economic Deal needs to:

Increase Economic Security We believe the common ground for a Fair Economic Deal should be increased economic security for middle income people, workers and the poor. As Jeff Faux observes, "It has become a cliche that workers must adjust to being churned through many companies, none of which will provide a secure working life. For Americans with confidence, connections, and degrees from prestigious colleges, this is an exciting prospect. But for most, the new economy means being in constant anxiety about their economic condition, as companies under pressure from brutally competitive markets abandon responsibility for health care, pensions, and job security."1 The booming economy of the mid-and late-1990s had a gap of 4,000,000 jobs still needed among the urban and rural poor. The economy contained a great deal of underemployment among wage earners and middle class citizens. Many wage earning and middle class families needed two people working to make ends meet. A large number of people were working part time when they wanted to work full time. Many were working in low skilled, dead-ended jobs. Many family providers had no health and other benefits, or were terrified at being just one pay check away from zero health coverage. The poor worried about decent child care, affordable housing and enough money to send kids to college. But so did most wage earning and middle income families.2 As a first step in increasing economic security, a Fair Economic Deal must acknowledge that the poor, wage earners and the middle class need not only quality education and training early on, as they begin their work lives, but also later as changing technology and shifting global competition require re-education and re-training.3 A Fair Economic Deal should provide federally financed initiatives carried out by the private sector at intervals throughout a citizen's work life, as needed by each person to maintain a cutting edge of competitiveness. A Fair Economic Deal can create new education and training opportunities over the lifetimes of workers as a means of forming coalitions among African-American, Latino and white urban ethnic constituencies. The lower middle class of white Americans without a college degree represent over fifty percent of the electorate.4 In the 1960s, many white urban ethnics were hostile to African Americans -- because they thought civil rights advances were at urban ethnic expense, especially in education, training, employment and housing. In the late 1970s, visionaries like Father Geno Baroni, HUD assistant secretary for neighborhoods, began creating alliances among urban ethnics, African Americans and Latinos -- through neighborhood-based programs that enriched their neighborhoods and encouraged them to work, and vote, in partnership. Father Baroni's vision was undermined by the separatist racial politics of the 1980s, which remotivated white urban ethnics to see minorities as their enemies. Today, we need to return to Father Baroni's healing vision. We must diffuse racial hostility and bring together multiracial urban constituencies in a win-win coalition in which they receive education and training investments and reinvestments in their human capital. The coalition should include persons in core cities and older suburbs who have formed common fronts in places like Minneapolis/St. Paul and Cleveland against losing resources to the new exurbs.5 A Fair Economic Deal must unite constituents on the historically proven need for public investments to generate much of the new education, training and job opportunity. Long term growth in America has depended critically on public investments. The federal government took the lead in investing in assembly lines, long distance radio transmission and railroads. President Eisenhower built the interstate highway system. In more recent years, the federal government has invested heavily in the development of rockets, computers, silicon chips and biotechnology. Yet, beginning in the 1980s, public investment has fallen in many areas. For example, from 1978 to 1998, real public spending on transportation and technology dropped from 2.6 percent to 1.6 percent of GDP. Recent polls consistently show Americans favor new public investments over tax cuts. Without such training and job generating public investments, today most citizens experience or see the everyday realities of dilapidated and overcrowded schools, jammed highways, overcrowded airports like LaGuardia and O'Hare, and reductions in civilian research and development.6 Can we secure a Fair Economic Deal voting majority around public sector-facilitated education and training over a worker's lifetime to maintain technological and global competitiveness and to modernize our aging public investment infrastructure? The answer may be yes, based on national surveys of voters by the Pew Research Center for People and the Press7 and especially by Albert H. Cantril and Susan Davis Cantril.8 For example, the Cantril surveys show voter disagreement philosophically on the role of government in the abstract. But the Cantril surveys also identify voter majorities for specific pragmatic government investments. Such investments include increased spending on job training, Head Start, teacher subsidies and college student aid. Over the 1990s, other national polls consistently showed support for job training, job creation and a bigger role for government in solving problems facing children.9 American history is supportive here as well. The most successful national public sector initiatives almost always have had very specific goals -- like creating Social Security, providing health care for the elderly, legislating the G.I. Bill for returning servicemen and landing astronauts on the moon. These findings fit well into our frame of program-selective education, job training, employment, racial justice and criminal justice investments in what works. Beyond education and training, re-education and retraining, a Fair Economic Deal needs to fight for higher, living wage jobs; create universal health care guaranteed by the federal government; structure a pension safety net that will hold up even in an insecure economy; and preserve the Social Security system. Public opinion polls support these policies. A minimal level of old-age security must be assured. We must oppose supply side attempts to divert Social Security funds to any scheme that can lose retirement funds in private stock markets.10 Strengthen Workplace Democracy A cornerstone of a Fair Economic Deal should be workplace democracy as a civil right. Many large corporations outsource work to smaller, nonunionized firms operating on small profit margins. These firms have turned a large portion of their employees into "contingent" workers. Here is where we find so many of the part time and temporary workers without health coverage or pensions. One result is that more workers were worried about losing their jobs in 1998, with lower unemployment, than in 1992, during recession. Surveys also show less worker loyalty toward their employers than they did a decade ago. Three times as many American workers say they want to be in a union than are in a union. A good model is the recent success of the Service Employees Union to unionized janitors in Los Angeles and elsewhere.11 Yet, present American U.S. labor law makes it extremely difficult to organize. Labor law reform is long overdue.12 "The right to organize and join a labor union should be reconceptualized as a civil right, so that employers are genuinely punished if they try to fire someone for organizing activity. One of the major explanations for America's weak labor movement is the relative ease with which employers may fire employees who are engaged in union organizing." A Fair Economic Deal should strengthen protection against termination by transferring jurisdiction from labor law to employment discrimination law. "[M]ost Americans will support the notion that an employee shouldn't be fired for a reason completely unrelated to job performance."13 A Fair Economic Deal needs the labor movement to recover the kind of decisive role that organized workers had in winning the five day week, the eight hour day, the minimum wage, Medicare and the 1964 Civil Rights Act. Historically, unions have secured national attention when they put forth a moral vision. For example, in the 1930s, unions tripled their membership under the rallying cry of "industrial democracy." In the 1960s, Martin Luther King helped mobilize workers into the civil rights movement by criticizing a system of "selfish ambition inspiring men to be more concerned about making a living than making a life." That legacy needs to be recaptured. Today, unions need to reverse the decline of their white, blue collar base at the same time that they welcome the current increase in membership of African Americans, Latinos and women -- to help reform the urban coalitions that were split in the 1980s. The AFL-CIO's call for amnesty for undocumented immigrants and its move to organize low wage workers are steps in the right direction.14 Create Global Protection for Workers A Fair Economic Deal must counterbalance the globalism that creates so much insecurity among middle income persons, wage earners and the poor. In the words of Jeff Faux, "The World Trade Organization (WTO) and so-called free-trade agreements such as NAFTA are really protectionist systems for global investors, which leave workers, farmers, and small business people to the mercies of a rigged market."15 Only the U.S. is in a position to create a long run dialogue that leads to global protection for workers, human rights and the environment. Labor rights should be enforced with trade sanctions, just as investor rights are."16 A good place to start is China. Through support from the Administration in the late 1990s, many in Congress and corporate America, we have "engaged" China, asserting that this step is good for both American business and democracy. But it has been good for neither. On the business front, for each ten percent increase in American investment in China, U.S. imports from China rise by seven percent and U.S. exports to China fall by two percent.17 On the democracy front, based on the State Department's annual review of human rights around the world, China's behavior has worsened under "engagement." Chinese workers have no union organizing rights. China has intensified its persecution of religious and spiritual movements. The Chinese system of "reform through labor," in which police can imprison a person for three years without trial or due process, is thriving. The Chinese government maintains tight control over freedom of speech, has increased its efforts to control the Internet and severely limits freedom of assembly.18 A Fair Economic Deal should insist that American workers do not lose jobs because of trade with China and that significant progress be made in labor and human rights in China. Without progress, trade sanctions should be invoked. As the mass protests at the 1999 WTO meetings in Seattle demonstrated, trade unionists, environmentals, advocates for the poor and community activists can coalesce around the lack of democracy in global corporations and the new international organizations that too often further corporate interests. A Fair Economic Deal needs the Seattle coalition. Reduce Inequality By creating a base of living wage employment workplace democracy, universal health coverage, pensions, and Social Security, and by then building on that base with lifetime education and training for higher paying jobs for middle income people, workers and the poor, a Fair Economic Deal should not only reduce economic insecurity but must start to diminish the enormous income, wage and wealth gaps between the rich and the rest of us. We need to recapture some of the national mood after World War II, when Americans from what NBC news anchor Tom Brokaw calls "the greatest generation" sought a more inclusive, equitable society in which everyone had a fair chance of making it.19 What "greatest generation story" can help recapture that mood of equality? The words of the story might include these:20

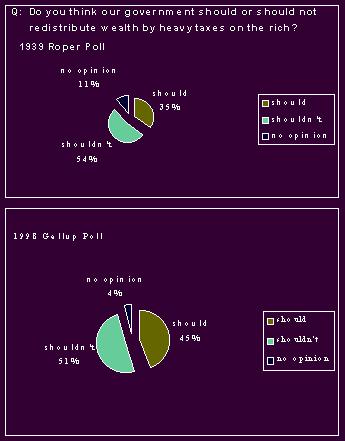

A Fair Economic Deal must question the excesses of the rich. When asked "Do you think our government should or should not redistribute wealth by heavy taxes on the rich," a recent Gallup poll showed fifty-one percent think we should not and forty-five percent think we should. The percent who think we should has increased over the past fifty years. (Figure 4.) Many "don't like the idea of government taking something that belongs to someone and giving it to somebody else." At the same time, "there also is a vague feeling that what the economy is producing in terms of rewards is not always in accordance with what people deserve." A Fair Economic Deal would acknowledge the Gallup findings by improving economic conditions for the poor, working class and middle class -- while not giving still more benefits to the rich.21 Figure 4

But a Fair Economic Deal also would take the "vague feeling" of undeserved riches and make it less vague. Here surveys by Professor Alan Wolfe at Boston College are helpful. The Wolfe surveys suggest that working and middle income Americans appear to be resentful of CEOs with excessive salaries and stock options. Such rewards to CEOs are perceived by many middle and working income people interviewed by Wolfe as disconnected from the efforts that go into securing them. Like "welfare queens," wealthy corporate "welfare kings" are perceived by many average Americans as not earning their money. This, suggests Wolfe, makes the rich politically vulnerable -- given the tremendous present income, wage, wealth and equity gaps. Wage earner and middle income families, including those with both parents working, may respond to messages like "reduce affirmative action for the rich" and "get corporations off welfare." Workers can be further motivated by the fact that their CEOs now get, on average, 400 times their pay, while in 1980 CEOs got forty times their pay. Americans can be made aware that large majorities already exist in five European countries and in Japan for public policies to reduce economic inequalities.22 Although not scientific samples, recent focus groups with working and middle class people (earning between $20,000 and $60,000 per year) support Wolfe's conclusions. In the focus groups, a large majority viewed "corporate greed" as "equally important" to or "more important" than "big government" as a cause of economic woes. For this working and middle class income group, large numbers of people (among Republicans, Democrats and Independents) believed that corporate behaviors like massive downsizing, cutbacks on workers benefits and decisions to send U.S. jobs overseas to China and other places were serious enough to warrant purposeful government action.23 Purposeful government action is needed, as well, in those industries that could help in the task of replicating and communicating what works for the truly disadvantaged. The most obvious example is corporate media. As we have seen, many Americans have lost confidence in corporate network media. The lack of confidence was heightened by the major networks' inaccurate reporting in the 2000 campaign -- for example on the Florida returns. The shortcomings of the networks are complemented by the exorbitant charges for political ads by their local affiliates. In the words of columnist David Broder, "the local broadcasters continue to treat politics as a profit center, not a public responsibility." Lobbyists for the nine multinational corporations that control almost all media in America are among the most powerful in the nation's capital. But we can begin to build on the lessons of media reform movements in Canada, Sweden, France, Australia, New Zealand and India. Through the Internet and town hall meetings, we can begin public dialogue on whether, as former NBC president Lawrence Grossman advocates, big media should pay for the current free use of the air electromagnetic spectrum. This amounts to billions of dollars in yearly taxpayer subsidies -- almost enough to replicate Head Start to scale. And we need to debate revamping antitrust laws to set limits on media ownership, as media critic Robert McChesney proposes. Activism on this issue can bring together citizens from many different income levels.24 A Fair Economic Deal needs to return this spirit of the American Revolution. Few Americans recall that "we the people" fought the American Revolution as a protest against both distant big government and unaccountable big corporations:25

In America's first hundred years, a corporate charter could only be approved by a state legislature, usually by a two-thirds vote. Few charters were awarded. But gradually the rich and powerful became less accountable to the people. Today, we need to re-establish "citizen rule over our government, our economy, and our environment."26 Yet, while establishing rule by middle income, working class and impoverished citizens over corporations, a Fair Economic Deal should be advocating a probusiness policy. These are not mutually exclusive goals. Most businesses in America are unincorporated enterprises -- individuals, sole proprietorships, partnerships, co-ops or other forms of operation. Businesses are central to the American experience -- and to the kind of old fashioned, democratic American values and competition that big corporate power today denies.27 Incorporate Campaign Finance, Voter Democracy and Communications Reform Movements The Fair Economic Deal must embrace campaign finance reform, voter democracy reform and better communication of what works to the average citizen. By removing monied interests, campaign finance reform can make it easier to pass legislation that increases economic security and reduces inequality. By implementing new voter technology and changing the way we elect presidents, a voter democracy movement can put more power in the hands of average people, and so help pass legislation that improves their economic well being. By showing citizens that we already possess viable solutions, a movement to communicate what works can increase citizen confidence in a Fair Economic Deal and suggest ways to save taxpayers money (as is the case with diversion of nonviolent offenders from prison in the conservative state of Arizona). By incorporating these movements, we expand the base of middle income, working class and impoverished constituents for a new political alliance. (See Unequal Protection: Corrupted Democracy.) Debate Public Morality As part of a Fair Economic Deal, the immorality of many public policies should be driven home by local clergy in poor, wage earner and middle income neighborhoods. Knowledge of what works and how to communicate it needs to be supplied to local congregations by national organizations - like the National Council of Churches. There already is great awareness of the contradictions of prosperity and the need for justice among all religious denominations in America. Many are motivated. They now need to partner in a way that recognizes how any "faith based" policy requires advocacy strategies and real resources. (See The Lack of Morality in Public Policy.) Notes and Sources Jeff Faux, "What Kind of America Do We Want?" in Robert L. Borosage and Roger Hickey, editors, The Next Agenda (Boulder and Oxford: Westview Press, 2001, p. 23). [Back] Peter Edelman, Searching for America's Heart (Boston and New York: Houghton Mifflin Company, 2001); Jeff Faux, "What Kind of America Do We Want?" in Robert L. Borosage and Roger Hickey, editors, The Next Agenda (Boulder and Oxford: Westview Press, 2001). [Back] Jeff Faux, "The Economic Case for a Politics of Inclusion," paper prepared for the Eisenhower Foundation's 30th Anniversary Update of the Kerner Riot Commission (Washington, DC: Economic Policy Institute, 1998); Jeff Faux, "You Are Not Alone," in Stanley B. Greenberg and Theda Skocopol, editors, The New Majority: Toward a Popular Progressive Politics (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1997). [Back] Roger Hickey, "A Moment for Economic Security in an Age of Change," in Robert L. Borosage and Roger Hickey, editors, The Next Agenda (Boulder and Oxford: Westview Press, 2001, p. 346). [Back] Lawrence M. O'Rourke, Geno: The Life and Mission of Geno Baroni (New York: Paulist Press, 1991, pp. 107, 143); Jeff Faux, "The Economic Case for a Politics of Inclusion," paper prepared for the Eisenhower Foundation's 30th Anniversary Update of the Kerner Riot Commission (Washington, DC: Economic Policy Institute, 1998);Jeff Faux, "You Are Not Alone," in Stanley B. Greenberg and Theda Skocopol, editors, The New Majority: Toward a Popular Progressive Politics (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1997); and John Jeter, "Cities, Oldest Suburbs Becoming Allies," Washington Post, February 22, 1998. [Back] Jeff Faux, "What Kind of America Do We Want?" in Robert L. Borosage and Roger Hickey, editors, The Next Agenda (Boulder and Oxford: Westview Press, 2001, pp. 35-36). [Back] Sean Wilentz, "For Voters, the 60's Never Died," New York Times, November 16, 1999, p. A 31. [Back] Albert H. Cantril and Susan Davis Cantril, Reading Mixed Signals: Ambivalence in American Public Opinion About Government (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1999); David Broder, "Voters of Two Minds," Washington Post, September 26, 1999, p. B7. [Back] Alan Curtis and Fred R. Harris, The Millennium Breach (Washington, DC: Milton S. Eisenhower Foundation, 1998, Chapter 7). This publication is posted in its entirety under Publications. [Back] Jeff Faux, "What Kind of America Do We Want?" in Robert L. Borosage and Roger Hickey, editors, The Next Agenda (Boulder and Oxford: Westview Press, 2001, p. 39). [Back] Roger Hickey, "A Movement for Economic Security in an Age of Change," in Robert L. Borosage and Roger Hickey, editors, The Next Agenda (Boulder and Oxford: Westview Press, 2001, p. 355). [Back] Jeff Faux, "What Kind of America Do We Want?" in Robert L. Borosage and Roger Hickey, editors, The Next Agenda (Boulder and Oxford: Westview Press, 2001, p. 37). [Back] Richard D. Kahlenberg and Ruy Teixeira, "A Better Third Way," Nation, March 5, 2000, p. 15. [Back] Stanley Aronowitz, "Race: The Continental Divide," Nation, March 12, 2001, p. 25. [Back] Jeff Faux, "What Kind of America Do We Want?" in Robert L. Borosage and Roger Hickey, editors, The Next Agenda (Boulder and Oxford: Westview Press, 2001, p. 41). [Back] Jeff Faux, "What Kind of America Do We Want?" in Robert L. Borosage and Roger Hickey, editors, The Next Agenda (Boulder and Oxford: Westview Press, 2001, p. 42). [Back] Jeff Faux, "What Kind of America Do We Want?" in Robert L. Borosage and Roger Hickey, editors, The Next Agenda (Boulder and Oxford: Westview Press, 2001, p. 34). [Back] Michael Kelly, "Engagement's Unseen Eye," Washington Post, February 28, 2001, p. A25. [Back] Tom Brokaw, The Greatest Generation (New York: Random House, 1998). [Back] Jeff Faux, "You Are Not Alone" in Stanley B. Greenberg and Theda Skocopol, editors, The New Majority: Toward A Popular Progressive Politics (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1997). [Back] Steve Pearlstein, "Should the Tax System Redistribute the Wealth?" Washington Post, March 11, 2001, p. H1. [Back] Alan Wolfe, "The New Politics of Inequality," New York Times, September 22, 1999, p. A27.; Sophie-Body Gendrot, "Tocqueville Revisited," in Lynn A.Curtis, editor, American Violence and Public Policy (New York and Oxford: Rowman and Littlefield, forthcoming 2002). [Back] Jim Hightower, If the Gods Had Meant Us To Vote, They Would Have Given Us Candidates (New York: Harper Collins, 2000, p. 337). [Back] Milton S. Eisenhower Foundation, To Establish Justice, To Insure Domestic Tranquility: A Thirty Year Update of the National Commission on the Causes and Prevention of Violence (Washington, DC: Milton S. Eisenhower Foundation, 1999). This publication is posted in its entirety under Publications. Also see Jim Hightower, If the Gods Had Meant Us To Vote, They Would Have Given Us Candidates (New York: Harper Collins, 2000); and David Broder, "Where the Money Goes," Washington Post, March 20, 2001, p. A27. [Back] Jim Hightower, If the Gods Had Meant Us To Vote, They Would Have Given Us Candidates (New York: Harper Collins, 2000). [Back] Jim Hightower, If the Gods Had Meant Us To Vote, They Would Have Given Us Candidates (New York: Harper Collins, 2000). [Back] Jim Hightower, If the Gods Had Meant Us To Vote, They Would Have Given Us Candidates (New York: Harper Collins, 2000, p. 311). [Back] |